Almost as soon as he put the phone down, Gerit Hardenberg heard the low rumbling sound coming across the river. It grew, like the side of a mountain falling on top of him, and then faded into silence.

What Gerit Hardenberg could not hear was the eerie pinging noise that came from the flakes of rust peeling off weathered steel or the jarring screech of metal moving slowly across metal.

What he could not see was the men holding their hands to their ears to block out the noise or the look of terror in their faces as they saw things that should have been firm and solid begin to move and parts of the metal’s colour change to a strange kind of blue.

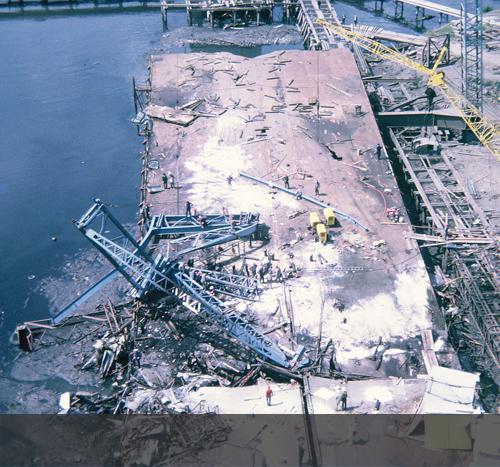

The whole 2,000-ton mass plummeted into the Yarra mud with an explosion of gas, dust and mangled metal that shook buildings hundreds of yards away. Homes were spattered with flying mud. The roar of the impact, the explosion and the fire that followed could be heard more than two miles away.

But by the time men, who had been hurled into the river below, had surfaced from the depths all they could hear was the clanging of loose metal and the crackle of the fire. As they clawed their muddy, oil-soaked bodies out of the river those who could walk or talk began searching and calling out for their mates.

The huge span lay like a broken and beached battleship beside them and, as they heard the first shrill sounds of the sirens, they knew it was time to comfort the injured and count the dead.